San Franciscans of Japanese descent during forced evacuation of the city in 1942. Photo by the Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority.

African Americans have been a part of San Francisco since before the Gold Rush. The city’s Black population saw its greatest increase, however, during World War II. Hailing primarily from Louisiana and Texas, the newcomers had been recruited to work in Bay Area shipyards. Many settled into homes in the Western Addition recently vacated by San Franciscans of Japanese descent who had been forced, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, to relocate to internment camps.

Over the following two decades, a visible African American presence established itself in the Western Addition neighborhood around Fillmore Street. This included a vibrant jazz and rhythm-and-blues nightclub scene that featured such artists such as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Count Bassie, Thelonious Monk, and Ella Fitzgerald. When Justin Herman took control of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency in 1959, however, he oversaw the razing of much of the Fillmore and the forcible removal of Black residents from the neighborhood, bringing an end to the Fillmore jazz era. James Baldwin’s 1963 documentary, “Take This Hammer,” addresses the fallout; it can be seen online for free.

Ella Fitzgerald and Fillmore celebrants in the 1950s. Courtesy the Red Powell/Reggie Pettus Collection.

Elizabeth Pepin and Lewis Watts have been working for many years to rescue the neighborhood’s Black music history – including Pepin’s work as associate producer on the 1999 KQED documentary, The Fillmore. In 2006, they published Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era. The book was released with a companion website and an exhibit that traveled to venues including the Museum of Performance and Design in San Francisco and the California African American Museum in Los Angeles.

Featured on the cover of the 2006 edition were, l-r: John Handy, Pony Poindexter, John Coltrane, Frank Fisher at Jimbo’s Bop City in the 1950s. Photo by Steven Jackson Jr.

Performing at the Herbst Theater in conjunction with the 2006 publication of Harlem of the West were John Handy (2nd from left) and Frank Fisher (3rd from left) who had appeared on the book’s cover. Photo courtesy Lewis Watts.

Currently, Pepin and Watts are preparing a revised edition of the book. It will feature a new design and Introduction, as well as additional material based on the oral histories they have recorded and photographs they have collected since the book was first published.

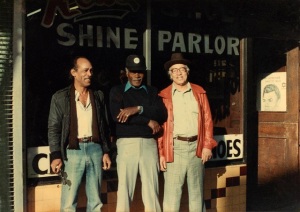

In part, it was photographs that first prompted the creation of the book – specifically, pictures that hung on the walls of Red’s Shine Parlor, a shoeshine business on Fillmore Street. Following owner Red Powell’s untimely death, his photographs were rescued by Reggie Pettus, owner of the New Chicago Barbershop across Fillmore street from Red’s Shine Parlor. Pettus, in turn, made them available to Lewis Watts.

Red Powell (far right) in front of his shoeshine parlor in the 1960s. Courtesy the Red Powell/Reggie Pettus Collection.

Many of the photos lacked information about the photographers and the people and places they portrayed. Elizabeth Pepin collaborated with Watts, who teaches photography at UC Santa Cruz, to identify the photographs. Pepin pursued her research at a time when little scholarship had done about African American history in San Francisco aside from a handful of works such as Douglas Henry Daniels’ Pioneer Urbanites and Albert Broussard’s Black San Francisco. Also at that time, Bay Area archival repositories such as the California Historical Society, the Bancroft Library, and the San Francisco History Center had little material about the city’s Black history.

Since the initial publication of the book, Pepin and Watts have discussed their work with a wide range of audiences. In response, they have received ongoing offers of additional photographs and oral history recording sessions. It was this new content that prompted their decision to release an expanded version of their book – as well as audio files of some of those oral histories in future iterations of their website. As Pepin explained to me,

The Fillmore was pretty much gone by the time I entered the world. I didn’t feel I had the right to put my voice into that. Obviously, I’m choosing out of all the interviews. But really the book is written by the people who lived the history. I feel very strongly that this stuff needs to be available to the public. I think that there are many, many more stories to be told in the Fillmore. It’s important that this material be made available so that other people can put it toward their own projects.

Pepin and Watts’s work is especially pertinent in light of the failure of other attempts to capture and communicate the Fillmore’s African American past. In 1995, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, which had previously decimated the Fillmore neighborhood, launched the mismanaged Fillmore Jazz Preservation District project. The mandate had been to commission permanent interpretive art installations, offer financial support for Black businesses, and establish jazz venues such as Yoshi’s as well as the Jazz Heritage Center (where material from Pepin and Watts’s work has been exhibited), but the results have been mixed. The neighborhood further suffered when a Community Benefit District, which was established in 2006 to promote Fillmore heritage and businesses, was shuttered in 2012 following infighting among the area’s businesses owners and residents.

As part of the Fillmore Jazz Preservation District project, this sidewalk marker outside the Fillmore Auditorium originally read, “Malcolm X Spoke At The Fillmore Auditorium, 1962.” The brick that featured the name “Malcolm X” has been replaced, but his name has not. 2012 photo by Drew Bourn.

Such disappointments make Pepin and Watts’s efforts to document and share the Black history of the Fillmore all the more vital. If you have photographs or can help identify persons and places in Pepin and Watts’s existing photograph collections, or if you might be willing to share your recollections of the period, please contact Pepin and Watts. Such contributions are welcome as they prepare their new and expanded edition of Harlem of the West.